Rosalind Franklin and her work on virus structures

An exhibition to mark the centenary of Rosalind Franklin’s birth on 25 July 1920

Introduction

Rosalind Franklin is probably best known for her research on the structure of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) but in this online exhibition we aim to highlight her investigations into virus structures from 1953 onwards. This work in many ways was a continuation of Franklin’s earlier studies of DNA and the structure of carbons, as she used and pioneered techniques in X-ray crystallography in all three areas of research.

Rosalind Franklin on holiday in the Alps. Photograph taken by her friend and colleague in Paris, Vittorio Luzzati

Franklin’s first professional scientific work explored the molecular structure of coals, graphite and other carbons. After graduating from Cambridge University (1941) Franklin gained a research fellowship at the University, then a research position at the British Coal Utilisation Research Establishment (1942) where she began investigating coals. She was awarded a PhD for this work in 1945.

In 1947, Franklin went to Paris to take up another research position at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'Etat (Central Laboratory of State Chemical Services). There she led a research group on X-ray diffraction studies of carbons.

“In a series of beautifully executed researches she discovered the fundamental distinction between carbons that turned into graphite on heating and those that did not, and further related this difference to the chemical constitution of the molecules from which the chars were made”

- J D Bernal in ‘Dr Rosalind E Franklin’, Nature, vol 182 p.154, 19 Jul 1958

Photograph by Peter Fisher

In 1951 Franklin was awarded a fellowship at the newly established Biophysical Laboratory at King’s College London to pursue a different subject - deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

Franklin working with a research student, Raymond Gosling, built specialist equipment for an X-ray diffraction laboratory at King’s College and undertook systematic investigation of DNA. They first discovered that there were two forms of DNA: an A form (existing when DNA has a relative humidity of around 75%); and a B form (when DNA has a relative humidity of more than 75%).

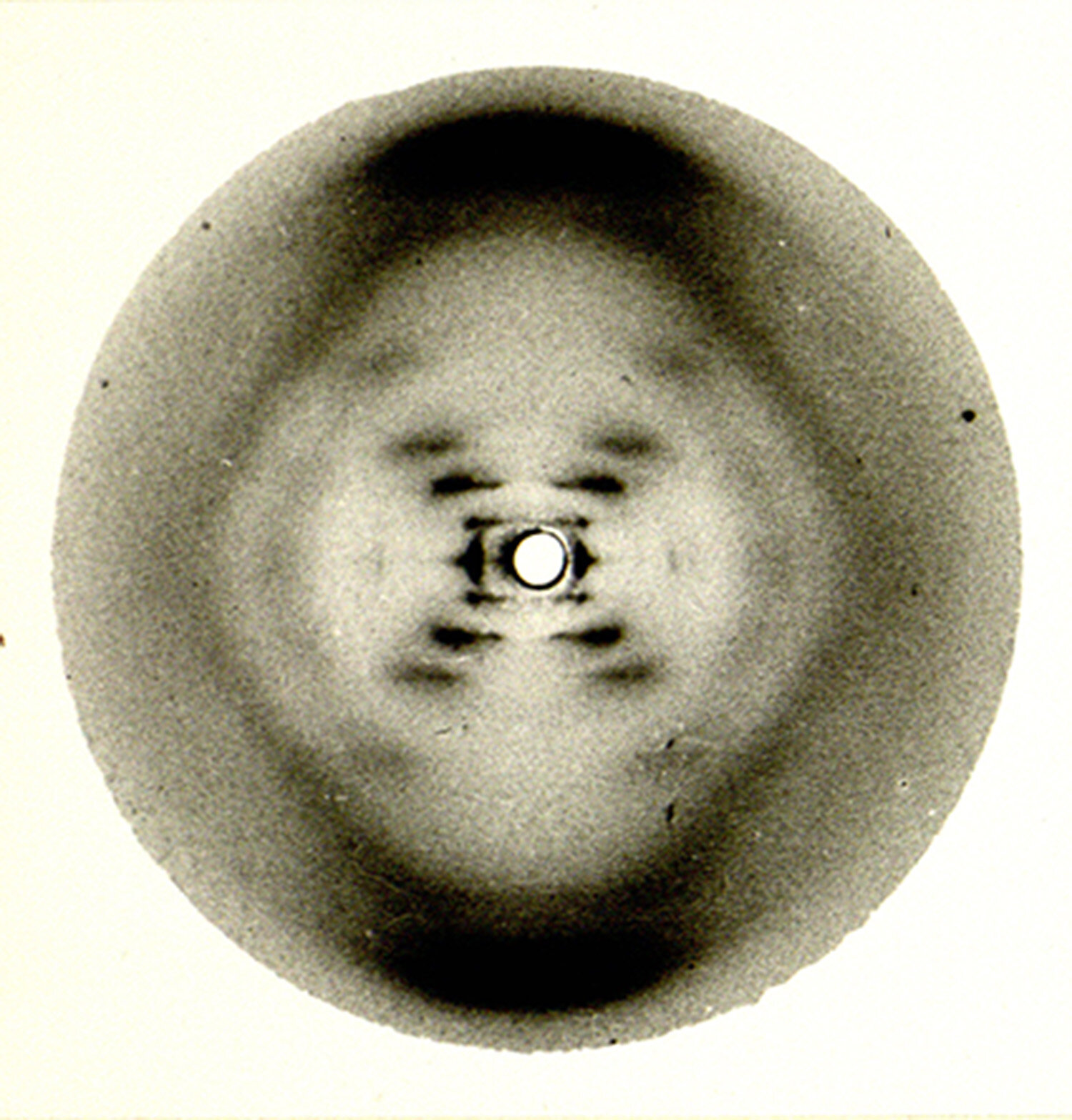

Franklin's X-ray crystallography photograph of the B-form of DNA (at more than 75% relative humidity) showing the double helix

From the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 1/3

“The careful, systematic experimental work, which made possible the characterisation of the two states of DNA, also led to the production of the best specimens”

- Aaron Klug in ‘Rosalind Franklin and the Discovery of the Structure of DNA’, Nature, vol 219, no 5156, 24 Aug 1968. In the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 6/1

By 1953, Franklin had X-ray crystallography photographs of both the A and B forms, and whilst the B form showed a double helix she was uncertain about the A form. Franklin and Gosling submitted their two papers on the A and B forms to Acta Crystallographica in March 1953 (though they were not published until September).

As Franklin and Gosling continued their investigation of the structure of the A-form of DNA, without their knowledge Maurice Wilkins (also at King’s College London and working on DNA) showed Franklin’s photograph of the B-form to James Watson who was visiting King’s College London in January 1953. Then in February 1953 Max Perutz (at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge) let James Watson and Francis Crick see his copy of the Medical Research Council’s report summarising the work of researchers including Franklin.

Crick and Watson had been working on the DNA puzzle at the Cavendish Laboratory, and Franklin’s unpublished data enabled them to build their model of DNA as a double helix.

“Watson and Crick seem never to have told Franklin directly what they subsequently have said from public platforms long after her death – that they could not have discovered the double helix in the early months of 1953 without her work”

- Brenda Maddox in ‘The double helix and the ‘wronged heroine’’, Nature, vol 241, 23 Jan 2003

Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins jointly won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for their work on the structure of DNA "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material."

Nobel Prize winners, 1962

l-r: Maurice Wilkins, John Steinbeck, John Kendrew, Max Perutz, Francis Crick and James Watson

Churchill Archives Centre, the Papers of Max Perutz, PRTZ 6/2/15

Obituary of Rosalind Franklin by J D Bernal, 19 April 1958

From the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/31

Birkbeck College

In March 1953, at the invitation of Professor J D Bernal, Franklin transferred from King’s College London to Birkbeck College’s crystallography research laboratory. There she directed research on X-ray diffraction studies of plant viruses, particularly the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), until her early death in 1958.

Research and teaching in crystallography did not take place in the main Birkbeck College building (where the rest of the Physics Department was located) but in 21, 22 and 32 Torrington Square due to a lack of space.

“By the time the building was completed the need for teaching and research had grown so much that it was already too small"

- R Furth, Bulletin of the Institute of Physics, July 1954

Birkbeck College main building, occupied by the College in 1951. Built after many of the College’s buildings had been destroyed during the Second World War

Image from ‘The Physics Department of Birkbeck College (University of London)’ in the Physics Bulletin, Vol. 5, No. 55, 1954 (in the Franklin Papers at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 5/25)

© IOP Publishing. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved

Rosalind Franklin’s laboratory/office was in 21 Torrington Square. To start with Franklin worked alone, but in 1955 Bernal successfully obtained a grant from the Agricultural Research Council to continue the work on viruses and to employ two assistants.

John Finch (who took the below photographs) began working with Franklin in January 1955 and Kenneth Holmes joined the team in July 1955. A C Page (technician) also joined the team in September 1955.

In addition, Aaron Klug began collaborating with Franklin in 1954-1955, and gradually transferred his research interests from protein crystallography (the original topic of his fellowship) to virus structures. Franklin and Klug had met on the attic stairs of 21 Torrington Square where they occupied adjoining rooms.

Rosalind Franklin’s office/laboratory in 21 Torrington Square. Copyright: John Finch/MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

“the attic rooms in which we began…leaked sometimes when it rained heavily, but provided a rather peaceful place for Rosalind Franklin to exercise her great ingenuity and skill at preparing better and better specimens and for myself to contemplate some of the theoretical problems involved in the helical diffraction analysis. The X-ray tubes were down in the basement and sometimes the condensation on the pipes resulted in drops of water falling from the ceiling and I have a vivid picture of Rosalind sitting under an umbrella carrying out the delicate operations for setting a TMV camera.”

- Aaron Klug in ‘Professor Bernal and Virus Research at Birkbeck College’, Summer 1968. In the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/37

Rosalind Franklin’s note on furniture required for her laboratory in the attic of 21 Torrington Square, 16 Dec 1953

Churchill Archives Centre, the Papers of Rosalind Franklin, FRKN 2/31

X-ray Crystallography Equipment

The apparatus needed to carry out X-ray crystallography was fundamental to Franklin’s work in identifying the structures of carbons, DNA, and plant viruses. Franklin took a central role in ordering, customising and designing the equipment.

Before starting in her new role at King’s College London, Franklin (writing from Paris) corresponded with Professor J T Randall about the equipment that she needed to carry out research on the structure of DNA.

When Franklin transferred from King’s College London to Birkbeck College in March 1953, she again took the lead in arranging and customising the equipment that she needed.

First page of a letter from Rosalind Franklin to Professor J T Randall about X-ray equipment for her research at King’s College London (sent whilst she was still in Paris), 8 July 1950

Churchill Archives Centre, the Papers of Rosalind Franklin, FRKN 5/30

“The first photographs were taken on a Phillips microcamera modified by Franklin for low angle work using one of the Ehrenberg-Spear X-ray tubes which had been developed at Birkbeck some years before. Later Franklin introduced the Beaudouin X-ray tube with which she had become familiar in France…Despite the great headaches this apparatus gave everyone, not least the Professor [Bernal], who had voluminous correspondence with the manufacturers about it, it proved invaluable.”

- Aaron Klug in ‘Professor Bernal and Virus Research at Birkbeck College’, Summer 1968. In the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/37

Diagram of Philips microcamera used by Franklin for her virus research at Birkbeck College, c.1953-1955

From the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 5/30

This camera (in the diagrams below) to be constructed for Franklin’s virus research [c.1955] was to be “generally similar to the N. A. Philips X-ray camera in type, but to differ in that it can accommodate four different film sizes” [to work with a fine focus Beaudouin X-ray tube].

Diagrams of a camera to be constructed for Franklin’s virus research, undated [1955]

From the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at the Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 5/30

“From the experience of the Cambridge MRC unit...it is clear that the only such camera commercially available is the Buerger precession camera, modified according to the specifications of Dr M Perutz. We have recently had the occasional use of such a camera at the Royal Institution, by kind permission of Sir Lawrence Bragg. This arrangement is only possible temporarily, while some of the Royal Institution staff are on holiday, but has served to confirm the usefulness of the Buerger precession camera for our purposes.”

- From ‘The need for a Buerger Precession Camera for research on virus structures', funding request to the Wellcome Trust by Franklin and Klug [1956]. In the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 5/27

First page of a funding request to the Wellcome Trust asking for money to pay for a Buerger precession camera [to work with a fine focus Beaudouin X-ray tube] [1956]

In the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 5/27

“one felt engaged in a constant battle with apparatus stretched to the limit of performance, a battle which had to be won to produce X-ray pictures good enough to be used quantitatively and so interpreted. In fact a good deal of the success of the investigations can be attributed to the introduction by Franklin of these non-conventional X-ray tubes and cameras, which provided high intensity and fine resolution from weakly scattering specimens.”

- Aaron Klug, ‘Professor Bernal and Virus Research at Birkbeck College’, Summer 1968. In the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/37

Virus structures

When Franklin took up her post at Birkbeck College in March 1953 she began work on analysing the structure of Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV).

TMV, which affects the tobacco plant, was the first virus to be discovered in 1892-1898. Later J D Bernal (head of the crystallography laboratory at Birkbeck College) carried out initial X-ray diffraction studies on TMV with Isidor Fankuchen, the results of which were published in 1941. These studies showed that the virus was made up of identical units of protein, but did not explain how these units fitted together.

“Since the classical studies of Bernal and Fankuchen on the X-ray diffraction of Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV), much progress has been made in the techniques of interpreting complicated diffraction patterns, and the ideas of micro-biologists concerning the structure of the simpler viruses have developed considerably. It therefore seems that the time has come to undertake a new investigation, by X-ray diffraction, of those viruses such as TMV which can be obtained in a well-orientated form... A suitable X-ray camera for this purpose has been constructed, and work on TMV specimens associated with varying amounts of water has already been started… Later we hope to be able to study other rod-shaped viruses, and, also, the smaller RNA-free fragments which are always found associated with preparations of TMV.”

- Extract from Programme of Research, 1954. In the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/32

Research photographs of Tobacco Mosaic Virus made using X-ray crystallography

From the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/31

As the below report from 1955 illustrates, Franklin’s research group also studied other plant virus structures including Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV), Potato Virus X, and Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus. TMV, CMV and Potato X Virus are all rod-shaped viruses but the study of Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus was part of an investigation into spherical viruses.

First two pages of ‘Agricultural Research Council Research Group on TMV: Progress report for 1955’

From the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/36

“Franklin took up the study of what is probably the most thoroughly studied of the plant viruses – that of Tobacco Mosaic disease – and almost at once, using the techniques she had already developed, made notable advances in it. She first verified and refined Watson’s spiral hypothesis for the structure of the virus. She then made her greatest contribution in locating the infective element of the virus particle – its characteristic ribose nucleic acid….She was able for the first time to set out the structure on a molecular scale of a particle which if not in the full sense alive is capable of the vital functions of growth and reproduction of other cells.”

- Obituary of Rosalind Franklin by J D Bernal in the Times, 19 Apr 1958. Quoted in Jenifer Glynn, ‘My sister Rosalind Franklin’ (page 153)

Franklin and her research group were the first to discover the full structure of TMV (which was the first virus structure to be discovered), and published articles on it and the other viruses they studied. They also constructed a model of TMV for exhibition at the Brussels International Exhibition in 1958.

The information on the structure of TMV “was of more than abstract interest. Once the internal configuration of the virus was known, the way it works could be understood. The protein surrounds and isolates the nucleic acid (RNA) until the virus has infected a host cell. Once inside the cell, the RNA is released from the protein and begins generating new virus – the dreaded infective process.”

- Brenda Maddox, 'Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA’, pages 259-260

Collaborations with other laboratories

Partly due to the fact that Franklin’s research group at Birkbeck College lacked a biochemist to prepare virus specimens they collaborated closely with researchers in Germany and California.

“This period of development in our own work coincides with a period of great advance in the study of virus structures in the laboratories of Berkeley (USA) and Tübingen (Germany). We are in close touch with workers in these laboratories, neither of which have facilities for X-ray diffraction work. They regularly send us their new preparations for study, and our results are closely interconnected with theirs.”

- ‘Agricultural Research Council Research Group on TMV: Progress report for 1955’, Churchill Archives Centre, the Papers of Rosalind Franklin, FRKN 2/36

Letter from Franklin to Professor G Schramm (Max Planck Institute for Virus Research, Tübingen) relating to specimens which Schramm had sent and Franklin visiting the Institute for Virus Research, 27 April 1955

Churchill Archives Centre, the Papers of Rosalind Franklin, FRKN 3/11

First page of a letter from Franklin to Dr Fraenkel-Conrat (Berkeley Virus Laboratory, University of California) relating to specimens and arrangements for visiting the Berkeley Virus Laboratory, 20 Apr 1956. Franklin had also visited the Virus Laboratory earlier in 1954

Churchill Archives Centre, the Papers of Rosalind Franklin, FRKN 2/35

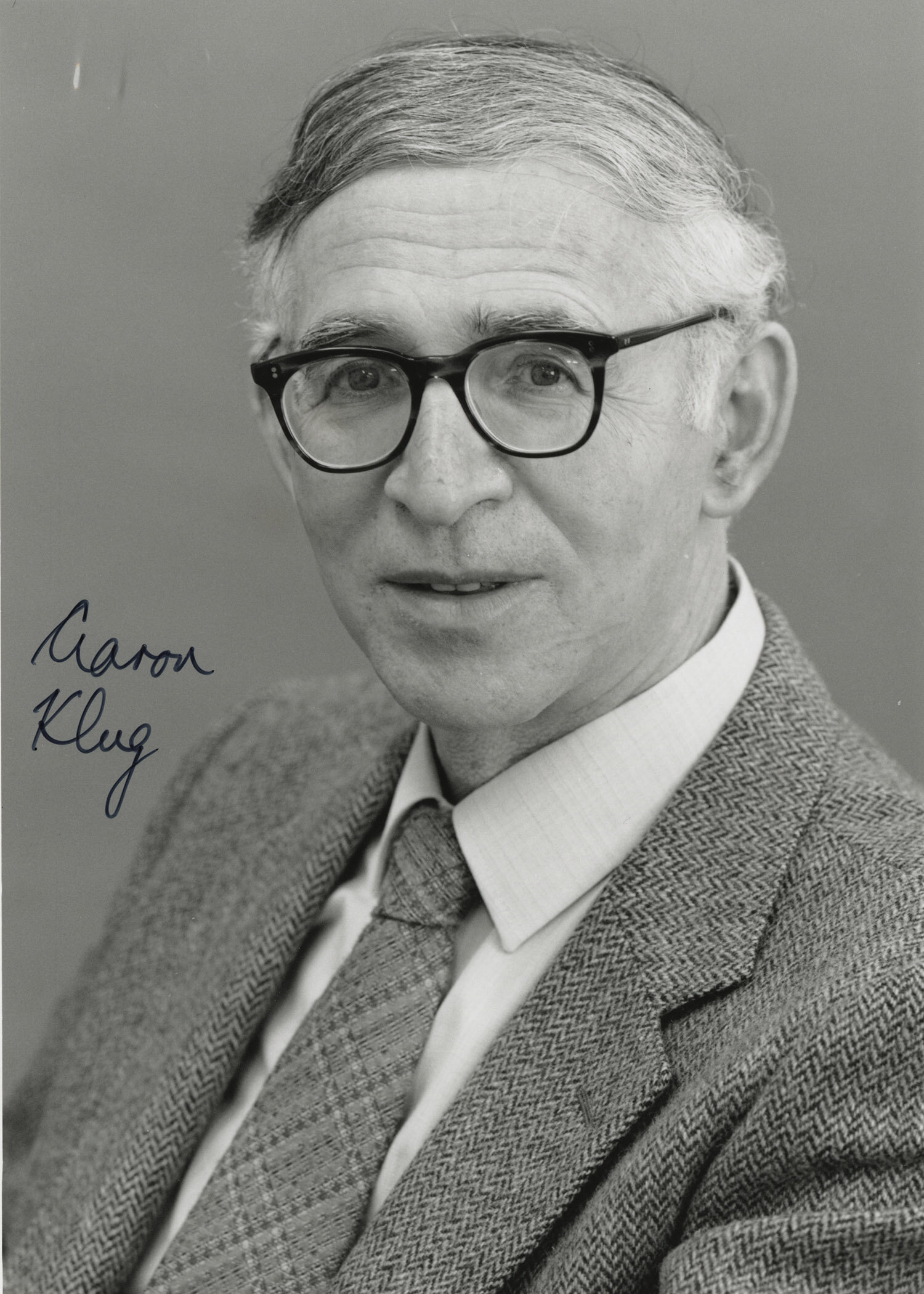

Aaron Klug

Aaron Klug started working with Rosalind Franklin after they met at Birkbeck Crystallography Laboratory in Torrington Square and he was diverted to the study of the structure of plant viruses (from the structure of proteins).

Portrait photograph of Sir Aaron Klug [c.1975-2000]

From the Papers of Aaron Klug at Churchill Archives Centre, KLUG 10/3/13

As described in the below letter from Franklin, Klug collaborated with her on the study of the structure of Tobacco Mosaic Virus. He was also responsible for work investigating the structure of Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus (a spherical virus).

Letter from Franklin to Professor Stanley (Berkeley Virus Laboratory, California) sending a manuscript on Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus, introducing Klug and asking if he could visit the Virus Laboratory, 8 Mar 1957

From the Papers of Rosalind Franklin at Churchill Archives Centre, FRKN 2/35

After Franklin’s early death in 1958, the rest of the Birkbeck research group (Klug along with Kenneth Holmes and John Finch) continued their work on virus structures, specifically looking at spherical structures. The Virus Research Group moved to the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge in 1962, where Klug contributed to the development of crystallographic electron microscopy (for which he won a Nobel Prize in 1982).

In response to the publication of ‘The Double Helix’ by James Watson in 1968, Klug wrote two papers for Nature entitled ‘Rosalind Franklin and the Discovery of the Structure of DNA’ (Aug 1968) and ‘Rosalind Franklin and the Double Helix’ (1974) to set the record straight about Franklin’s contribution to the discovery of the structure of DNA. In preparation for these articles Klug studied Franklin’s notebooks from her time at King’s College London (these notebooks are now held at Churchill Archives Centre as part of the Papers of Rosalind Franklin).

Want to know more?

You can explore Rosalind Franklin’s archive online via the Wellcome Library Digital Collections where the majority of the collection has been digitised. You can also explore the catalogue of Rosalind Franklin’s papers.

A digitised selection of Rosalind Franklin’s papers has been made available online by the United States National Library of Medicine.

In addition to the archive of Rosalind Franklin, Churchill Archives Centre also looks after the papers of Sir Aaron Klug and the papers of Max Perutz.

The Papers of J D Bernal are available at Cambridge University Library.

King’s Cultural Community and the Rosalind Franklin Institute have both celebrated Rosalind Franklin’s 100th birthday with resources including blog posts and podcasts. See their Twitter accounts (@CulturalKings and @RosFrankInst) and Instagram accounts (@CulturalKings and @FranklinInstitute) or search #Franklin100 for more information.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Wellcome Library who funded the digitisation of the Franklin papers and make them available through the Wellcome Digital Library. The Wellcome Trust also funded the cataloguing and conservation of the Papers of Sir Aaron Klug. Thank you to Jenifer Glynn, Professor David Klug, the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology and the Institute of Physics for granting Churchill Archives Centre permission to reproduce items in their copyright for this exhibition.