Keeping and making diaries

Historical sources and perspectives

This exhibition was curated by history students from Anglia Ruskin University, and produced to coincide with a two-day international conference on diaries to be held at Churchill College and online, 23 and 24 March 2022

Exhibition curators

Hanah Ansari, Josh Betts, Lewis Callan, Patrick Courtney, Megan Davies, Sophie Gentry, Nick Hosking, Sophie Kerridge, James Klima, Lucy McDonald, Adam McEwen, Callum Mclean, Evie Ridler, Hattie Seager-Pope, Alice Sheppard, Mia Stewart, Anna Thomas, Holly Waldman, Shannon Webb

Group A: Women diarists

By Hanah Ansari, Sophie Gentry, Lucy McDonald and Anna Thomas

Blanche Lloyd

This diary entry was written by Blanche, Lady Lloyd, wife to Lord Lloyd of Dolobran, Governor of Bombay from December 1918 to December 1923. The presidency of Bombay was an absolutely crucial role in Britain’s imperial toolbelt and helped impose Britain imperial rule abroad. Key moments in Lloyd’s administration include the handling of Indian nationalism as well as the arrest of Mahatma Ghandi.

Blanche Lloyd accompanied her husband in his travels abroad and describes in this entry one of the many strikes which took place in 1919. She describes a narrative of cotton workers moving from place to place gaining support and eventually numbering 100,000. She even expresses surprise that the protest has remained so calm and non-violent.

The issue of cotton production in this period of Indian imperial history is key and highlights unrest over the control of British monopolies on Indian production. Raw cotton was produced in India, exported to Lancashire where it was spun and then returned to India as cloth. Not only did this weaken the economy of India but created a reliance on British made goods, which many chose to boycott.

These protests also largely took place because of calls for Indian independence, some degree of which was promised at the end of World War One. Blanche Lloyd references these quite negatively in the phrase ‘…Home Rule agitators’. Home Rule would involve self-government away from the British-Indian government. These calls were largely ignored and the government in fact began to crack down using measures known as the Rowlatt Act which extended the powers of the police against protestors.

This piece is particularly interesting because it is from a female perspective, at this point in British life women still remained in a very secondary position in society. The extract will therefore inevitably include personal thoughts and feelings which may not have been socially acceptable for a women to express.

Diary of Blanche Lloyd, pp.11-12, January 1919

Reference GLLD 28/8

Transcript of an extract from Blanche Lloyd’s diary, January 1919

"her particularly forthcoming. We

had a select dinner party for her [Lady Chelmsford] in

the evening; the Martins, Curtises, Scotts,

Knights + Heatons + I think she really

quite liked it. and was very nice to

them all, so that they were pleased

too. This morning we took her down to

the Alexandra Dock to receive a

batch of Kut prisoners, + after this

ceremony was over, went with her to the

Mole, + escorted her on board her ship,

the Nagoya. rather crowded + not very big;

but they had reasonably good cabins,

+ there was much better deck space than

on board the Chyebema [?].

George was to have gone to Delhi to-

day, to attend the Viceroy’s conference of

Provincial Governors. met to discuss the Reform

Scheme. Unfortunately, however, a big strike

of employees in the cotton mills has just

broken out – over 100,000 of them – and

he does not feel that it is possible to

leave Bombay until this has been settled,

+ is at any rate on the road to a

solution.

Saturday 18. It has been a very

unpleasant + anxious week. the

strike has persisted, + there seems

to be no doubt at all that it is

being fostered + supported by the

Home Rule agitators. So far there has

Been wonderfully little disturbance: they

had to shoot one day at Mahui [?], +

one man was killed; yesterday there

was more shooting + two or three

were hurt. The military are helping

the police in small detachments – but

only because there are not enough

policemen. Considering the numbers that

are out, it is really rather wonderful

that it should have been possible

to maintain law + order during 10

days, with so little use of force.”

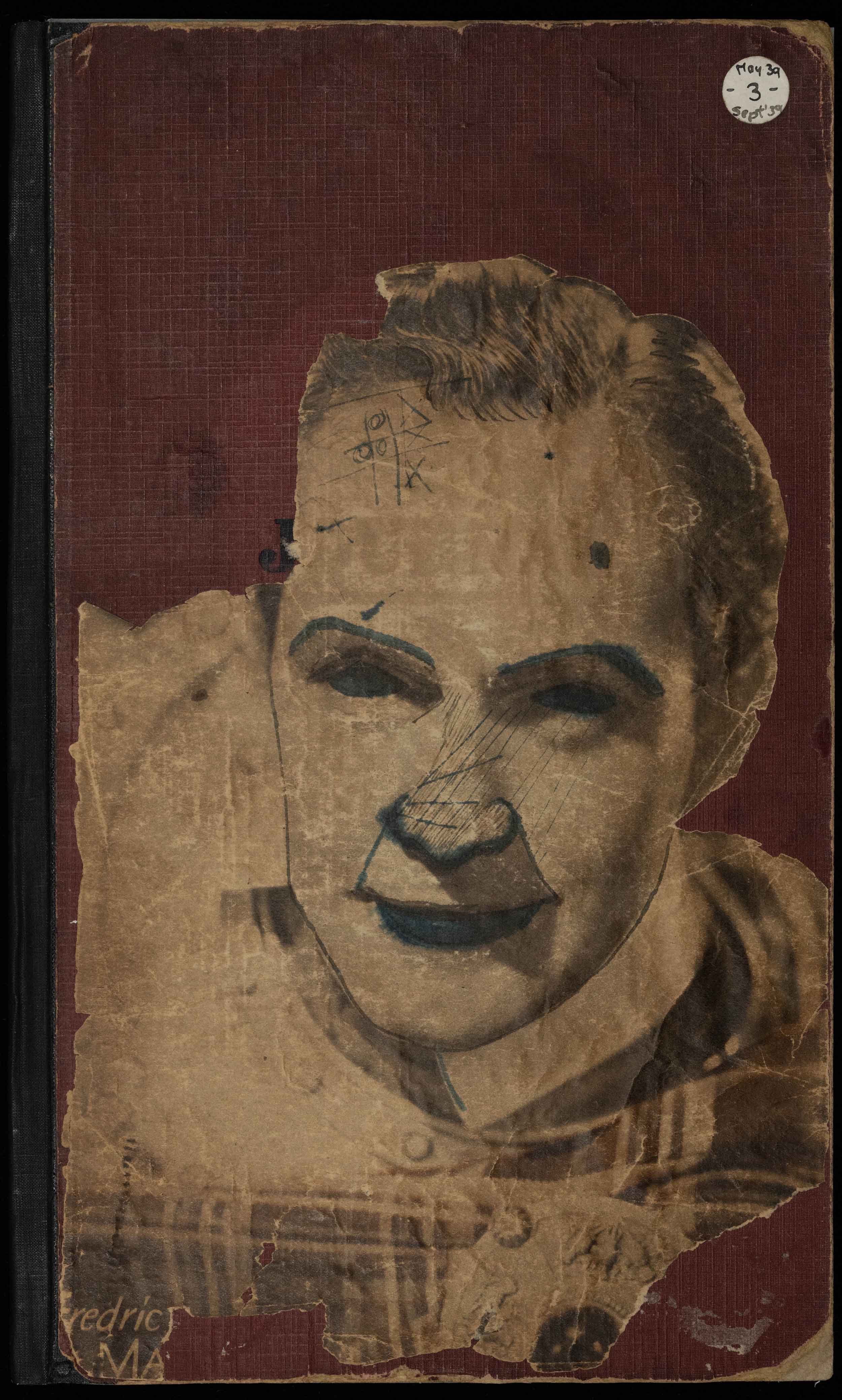

Childhood diary of Betty Thorpe (later the British agent in World War II code-named “Cynthia”)

Betty Thorpe is best known for her role in World War II, serving as a British informant under the pseudonym Cynthia. Prior to her war-related work however, Thorpe spent time enjoying life as a child in America (having been raised in Minnesota) and travelled across Europe in her early teenage years, accounts of which can be seen in a diary that she kept 1921-1924.

Of particular interest is page 1 of her diary, in which Thorpe describes her experience of an Abraham ‘Lincoln Play’ (former president of the US who famously tackled issues facing the nation over the American Civil War) in 1921. Not only does Thorpe’s experience highlight a sort of patriotism she clearly possesses at a young age (being American born, she describes it as ‘sad but very beautiful’), but also foreshadows her important role to come in World War II, with her description of Lincoln having ‘saved a soldier’. Another point to note is Thorpe’s repeated description of the play being ‘beautiful’. Perhaps her use of such repetitive language emphasises Thorpe’s child-like innocence and her young age.

Childhood diary of Betty Thorpe (later the British agent in World War II code-named “Cynthia”), 1921 – 1924

The Papers of Harford Montgomery Hyde, HYDE 2/1

“It was a very beautiful but sad play that we went to, Abraham Lincoln. The most beautiful scene was the Headquarters of General Grant. A plain brown hut with a dear little porch, covered with vines. The color of the sinking sun was delightful. The President Lincoln saved a soldier who was to be hung the next morning. It was sad but very very beautiful!”

Of her travels across Europe, one eye-catching aspect is that of her visit to ‘Deutschland’ (Germany) in 1923, on pages 114-115. Thorpe’s description of Germany’s ‘sloping mountains rising in a soft haze of violet blue to the silver sky and its gentle meadows and orchards (…)’ suggests a maturing in her writing compared with her 1921 account, using more adjectives and a story-like portrayal in her writing.

Such picturesque descriptions seem rather ironic considering Thorpe’s involvement in helping to defeat the Nazis during the war, which saw both destructions in Britain and Germany. The contrast between Thorpe’s childhood and adulthood in this way is interesting in showing how one’s life perspective can change over time, via the use of diaries.

Page 114 of childhood diary of Betty Thorpe (later the British agent in World War II code-named “Cynthia”), August 1923

HYDE 2/1

Page 115 of childhood diary of Betty Thorpe (later the British agent in World War II code-named “Cynthia”), August 1923

HYDE 2/1

Transcript of pages 114-115 of Betty Thorpe’s diary

Schwartzwald Hotel

Titisee, Black Forest

Germany.

We have come by motor farther up into the Black Forest region of Germany after an illness of which my lungs were seriously concerned. Titisee, in Baden is a small scattering of two or three forest hotels, perhaps as many as four shops / a rr [? rack railway] station and a beautiful lake nestled among the low hills covered with black forests.

Herr Adolf Schmidlin is painting a portrait of me / after having finished one of Jane and Daddy / beautiful things and absolute likenesses. We go rowing in little boats among the fish of the Titisee and like it so much. We took a trip to Neustadt, a tiny village of cu[c]koo clocks farther on. The walks in these pine forests among the fir needles are lovely and the odor of the pines will always linger as a dream of Deutschland!

Laeringenhob, [?]

Freiburg, Baden.

We returned to Freiburg last night, down through the great masses of forest which linger and dwindle to the old city’s edges. To say farewell to the old Rathohouse [Rathaus – Town Hall] and quaint winding [page 115] streets with its continual flow [of] beautifully garbed people / women / always in blue or green satin skirts, bright velvet bodices and the most fascinating of bonnets! To return to Switzerland means more or less safety / civilisation, with no extraordinary bargains, no freak money and really nothing beyond cleanliness, scenery and education!

So farewell Deutschland / with its sloping mountains rising in a soft haze of violet blue to the silver sky and its gentle meadows and orchards stretching far as eye can see on either side of the emerald Rhine! The fields and hills are softened by stately elms and poplars, while in the distance one may see the spire of some simple village church. The tiny cottages of the field laborers are sweetened by their age and delicate trailing vines which cling affectionately to their slanting rooves.

How sweet Deutschland looks with a veil of mist softening the hills and plains. The simple cattle grazing contentedly on the fresh green slopes, and the peasants quite as simple, toiling in the joyousness of their tiny plots, garbed in the quaint costumes of their forefathers know no other life than this and probably wish no other.

So it was we left Germany / left her to her fighting and her troubles, though one would never know there were any from the so succulently green country, the country of Goethe, and Wagner and the quarrels of all the empire once, now a rebellious republic!

August 20th 1923.

Mary Soames

Mary Soames (1922-2014)- youngest daughter of Winston and Clementine Churchill; married to Christopher Soames from 1947- 1987.

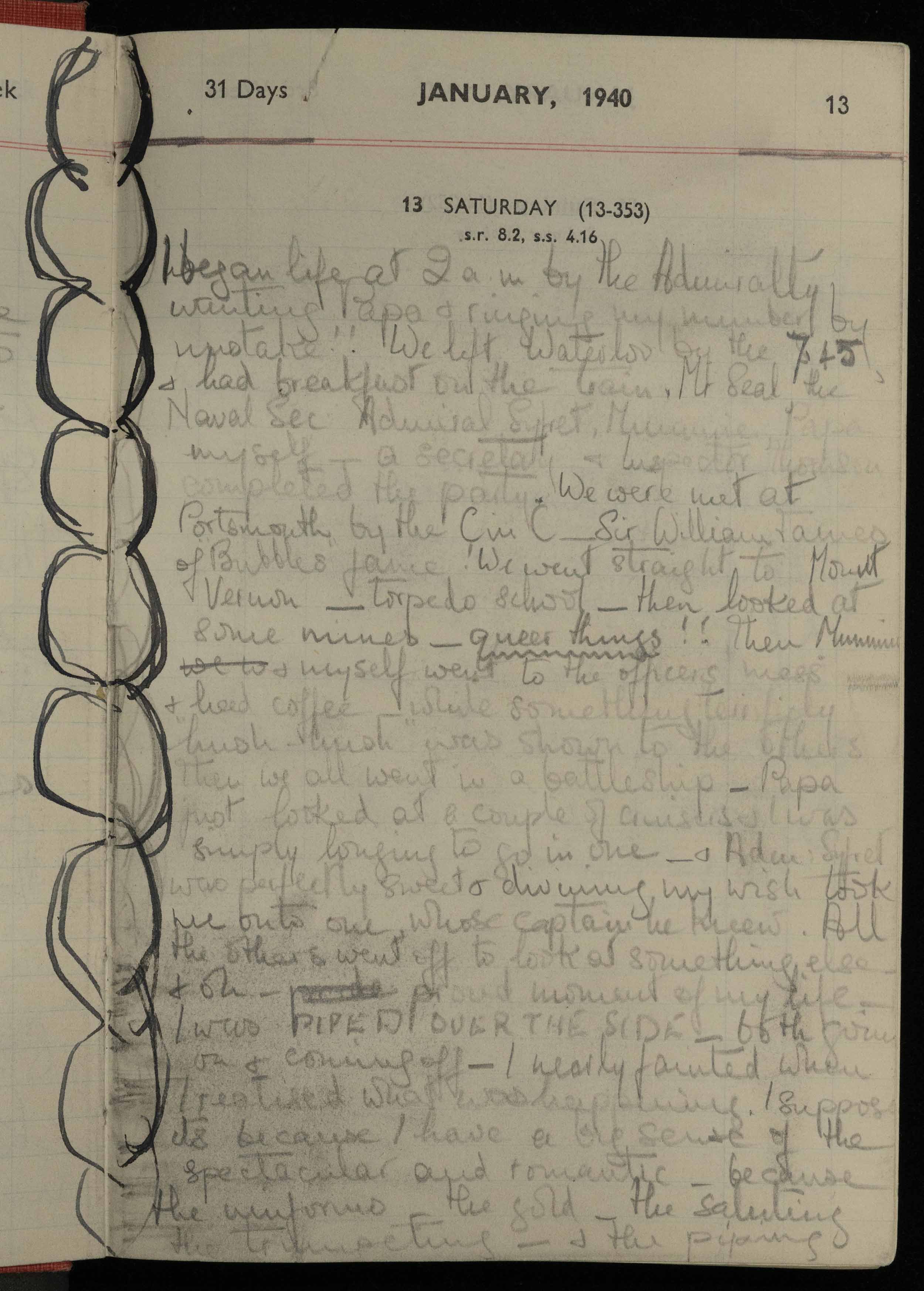

“I began life at 2am by the Admiralty wanting Papa & ringing my number by mistake!! We left Waterloo by the 7-45 &had breakfast on the train. Mr Seal the Naval Sec Admiral Syfret, Mummie, Papa, myself- a secretary and Inspector Thomson completed the party. We were met at Portsmouth by the C-in-C – Sir William James of Bubbles fame! We went straight to Mount Vernon- Torpedo school- then looked at some mines- queer things!! Then Mummie and myself went to the officers’ mess & had coffee- while something terrifically hush-hush was shown to the others. Then we all went in a battleship- Papa just looked at a couple of cruisers & I was simply longing to go in one- and Adm Syfret was perfectly sweet & divining my wish took me onto one whose captain he knew. All the others went off to look at something else & oh- proud moment of my life- I was PIPED OVER THE SIDE- both going on and coming off- I nearly fainted when I realised what was happening. I suppose it’s because I have a big sense of the spectacular and romantic- because the uniforms- the gold- the saluting- the trumpeting-& the piping.”

Saturday 13th January 1940

The Papers of Mary Soames, MCHL 1/1/2

This particular entry contains an account of the Churchills’ trip to Portsmouth, with Mary and her mother accompanying Winston as the First Lord of the Admiralty on an official visit.

This passage reflects Mary’s excitement. Her thoughts and feelings just flow out onto the paper. Sentences or words have been crossed out, or simply tail off as her train of thought shifts from one event to the next. Written informally, and apparently hastily in pencil, this entry gives a vivid sense of the occasion. She is clearly inquisitive and adventurous, with a rather romantic view of the Navy.

The account also reflects the atmosphere of the Royal Navy at the start of the Second World War seen through the eyes of a young girl. She clearly feels an honoured visitor, being piped on and off board and being aware that certain things were “Terrifically hush hush”! but she doesn’t seem to grasp the seriousness of the situation or the gravity of what she is being shown. For example describing mines as “queer things” she clearly is seeing this visit as more of a social event than a formal inspection.

This is clearly a very personal and spontaneous account. Her diary entries from her later life are more considered, objective and mature. As she became increasingly aware as she got older that they would be of interest for others to read.

Mary Soames 1979 diary

Lord Soames was the Governor of the British colony of Southern Rhodesia from December 1979 until 18th April 1980, when the country gained independence (now modern Zimbabwe). This area of their life was often captured within Mary’s diary entries during these years.

The Papers of Mary Soames, MCHL 1/1/39

This extract seen from 28th December 1979 gives a brief insight into the arduous discussions and subsequent events that surrounded Southern Rhodesia’s push for independence at the time.

In one particular section of the extract, Mary mentions the death of Robert Mugabe’s (a revolutionary politician in the fight for independence, who remained in power 1980-2017) ‘top general’, Josiah Tongogara (ZANLA* commander). She refers to his death in a car accident as ‘bad news: he really wanted a settlement [in the fight for independence]’, but also points out suspicions surrounding his death as an ‘accident’.

Next Mary refers to other past events of the week, in which this death seems to not be the only piece of bad news. She speaks of another crash that had occurred, as well as the worries she had surrounding the radio broadcasts from Mugabe in Maputo (Capital of Mozambique). She ends with how it all has ‘sent [her] to bed feeling we are surrounded by the powers of darkness’.

What is noticeable upon reading, however, is how this piece of writing about the fearful events surrounding her, is sandwiched in between two separate notes about going shopping- the above events were not the first thing she thought to write about. This suggests how, to Mary, while these events were significant, they had become something she was used to being a part of her life- political secrets and serious events- being born into the Churchill family.

*ZANLA- Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army.

Mary Soames’ diary. December 1979

Reference MCHL 1/1/39

Transcript of pages Mary Soames’ diary entries for 28th-29th December 1979

Friday 28th

Shopping spree in afternoon for house.

The death (on 27th) of Tongogara (Mugabe’s

top general) in a car crash – is bad news: he really wanted a settlement apparently.

Grave doubts are ex–pressed as to the nature of the ‘accident’.

One night this week the combination of the helicopter crash – Tongogara’s crash & reading the full text of Mugabe broadcast from Maputo. - sends me to bed feeling we are surrounded by the powers of darkness.

Sat 29th

Hair – food shopping & doing flowers. Emma a little bit better & 1/2 up.

Group B: Diary entries on the outbreak of the Second World War

By Josh Betts, Nick Hosking, Callum Mclean and Alice Sheppard

The diary of Mary Soames, 3 September 1939

This diary, written by Mary Soames (one of Winston Churchill’s five children) gives Mary’s personal thoughts about the declaration of war, on the 3rd of September 1939. She describes the declaration itself as at “11.15am announcement by P.M. of a state of war between Great Britain and Germany”.

This diary entry also expresses Soames’ disbelief that a major European war was occurring for a second time, containing concern for the soldiers who had already fought in World War 1 and would now have to do it again. It is also interesting to read the viewpoint she gives on the announcement and how similar it must have been for many at the time, being completely shaken by the declaration and unsure how to process it all occurring another time. She describes “standing in the living room” and looking outside her window, this detailed description of her view before her and her thoughts of the situation gives a very interesting insight into the lives of civilians at the time and the general reaction on this horrific announcement and situation.

The diary also includes an insightful format at the beginning of the diary, including a list of area codes (a three-digit number that is assigned to a geographical area) and sunset times, when compared to modern day diaries these aspects wouldn’t be included and it is an interesting read for visitors to see what information was deemed important for all to know at the time, alongside the description of the declaration of war itself further along inside this diary, especially as these features in diaries would have been used frequently during the time of war.

The Papers of Mary Soames, MCHL 1/1/1

The diary of Phyllis Willmott, 28 August - 4 September 1939

Phyllis Willmott was born in 1922 to a working-class family in East Anglia. During the outbreak of World War Two she was a teenager living in a house with 3 generations of Willmotts. Mentioned in her 4th diary when the first air raid sirens beaconed across East Anglia in the morning of the 4th of September 1939 at 1:00am and later at 3:00am she quoted that her grandad marched up and down across the garden with a broomstick stating he had no fear upon the declaration of British involvement in the war.

Phyllis Willmott’s diary across 1939-1940 educates us when analysing attitudes on the prospect of war. Willmott’s diaries showed a level of vulnerable honesty which were not written for public consumption 80 years ago to be analysed or assessed. These diaries were written to help her mentally off-load and describe her life. The diaries were exclusively hers. When analysing her diaries there is this clear sense that she isn’t an expert on geo-politics like Jock Colville or a member of high society like Mary Soames, you can see this with the ‘detailed’ illustrations of Germany’s military advancements towards Paris. This is still interesting to assess as Phyllis is a perfect example of the British public during the early stages of World War Two. This sense of naivety of the incoming hardships such as The Blitz and extended rationing. Phyllis’ diaries during World War Two shows us a pure documented experience of the war that other published works cannot.

The Papers of Peter and Phyllis Willmott, WLMT 1/4

The diary of John Colville, 10 September 1939

Sir John Rupert Colville, also known as Jock Colville, was a British civil servant and assistant private secretary to Neville Chamberlain from 1939-40, Winston Churchill from 1940-41 and again from 1943-45, and Clement Attlee in 1945. He would go on to be joint principle private secretary for Winston Churchill from 1951-55. The published version of his diaries was named The Fringes of Power based on his unique position and outlook he was afforded. The Jock Colville Hall at the Churchill Archives Centre was ultimately named in his honour.

‘The War has lasted a week now, and so I have decided to keep a diary’ was the first line of Colville’s diary, showing the understanding he had that the war would affect his life from the outset. Colville’s September 10th entry details his reasons for writing a diary, his day and what he did and his opinions on the people he meets. His diary is not however just a soulless record of events, he injects it with witty but often sardonic humour and much of his own personality as seen when he comments that his diary would be more entertaining during peacetime because of the glamour of his own social activities. Colville does follow patterns however naming the times he wakes up, ‘I got up at 7:30 and went to his service in Westminster abbey’ and when he meets others ‘Evelyn Fitzgerald arrived after 10.’ He also sometimes goes out of his way to give his opinions and extra context of whom he meets ‘the pretentious Maurice Ingram (who is now head of the Foreign Relations Dept in the Ministry of Economic Warfare) and his similarly charming American counsellor Herschel Johnson’.

The Papers of John Colville, CLVL 1/1

Group C: Second World War diaries

By Lewis Callan, Sophie Kerridge, Mia Stewart and Holly Waldman

Diary of Sir John Colville, 2nd May 1944

This extract has been taken from the diary of Sir John Colville, who was a British civil servant. He is best known for his diaries, which provide an intimate view of number 10 Downing Street during the wartime Premiership of Winston Churchill. Colville kept a diary from 1939 to 1957, parts of which have been published (The Fringes of Power:10 Downing Street Diaries 1939-1955). The original diaries are held at the Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge University, and, with the exception of the final volume, are open to the public.

This particular diary covers the period in which Colville was Assistant Private Secretary to Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1943-1945). From reading the diaries, Colville provides an in-depth look at the inner workings of Churchill’s Cabinet but in particular, it does appear that Colville does use intense strong language, which reflects the very intimate nature of Colville’s diaries. ‘Colville recorded in his diary that “Churchill, though he sometimes said nice things about me, never included in his recommendations that we were both Old Harrovians. I concluded that the old school tie counted even more in Labour than in Conservative circles.” This quote reflects significantly the importance of Colville during his tenure as Assistant Private Secretary to Churchill, which is also shown in his diaries, in particular, this extract mentions some very prominent figures like Sir Alan Frederick "Tommy" Lascelles, who would have significant prominence then as well in future long after Churchill.

“Still scheming with Tommy Lascelles about his Lord Lieutenancy of London. The PM to whom I spoke about it on Sunday was very amiable but seems to hanker after giving it to Camrose because he says that to give it to L[or]d Cranborne or the D[uke] of Norfolk (Grandfather’s suggestions) would mean gaining no extra allegiance for the Government. However he has given his authority to take soundings and I have agreed a course with Tommy, who will write and support the Cranborne idea and will mention a number of other names, including two suggestions of mine, the D[uke] of Wellington or Lord Trenchard.”

The Papers of John Colville, CLVL 1/6

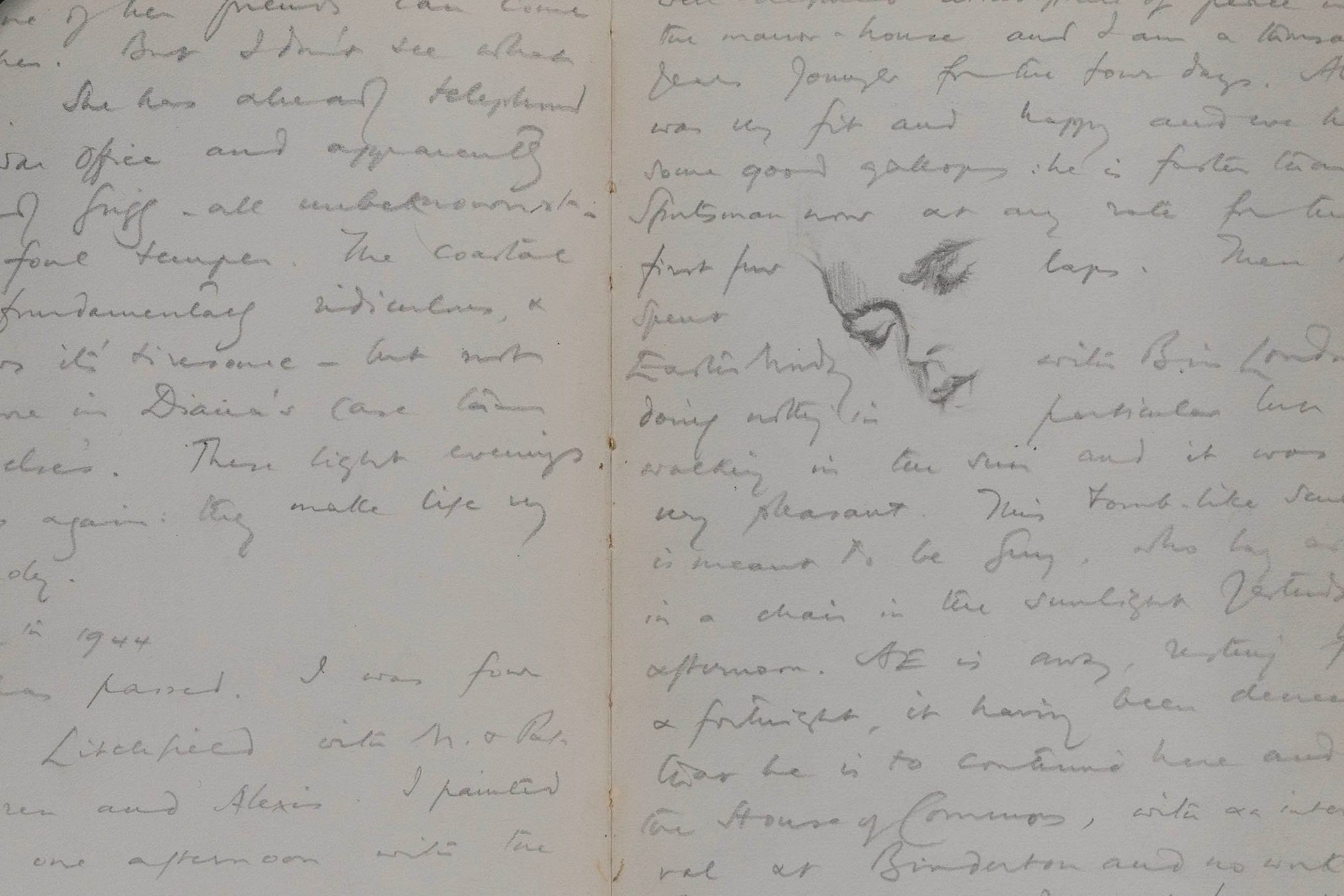

Diary of Valentine Lawford, 12th April 1944

Valentine Lawford in 1944 was Private Secretary to the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden. Lawford was Secretary to Lord Halifax prior to this and later to Ernest Bevin. In addition, Lawford attended many wartime conferences such as the Yalta Conference and the Quebec Conference. In these meetings he would act as interpreter for Winston Churchill. Lawford was a well-educated man, his specialisation in modern and medieval language meant he was well suited to be an interpreter. Lawford was a British diplomat; his presence and participation in crucial diplomacy during the Second World War make his diary extremely valuable reading. It brings an insider account and understanding of landmark events.

However, Lawford was also an artist. This secondary identity is clear to see in this diary entry. Lawford describes an idyllic retreat at Litchfield Manor with his mother and father and other presumably close friends or family members. Over his getaway, Lawford painted and sketched, he describes painting whilst the sun beats down on his work during the day. Within the handwritten diary entry is a beautifully detailed sketch. Lawford does not offer any reference to this sketch but with its placement inside the paragraph it would be plausible to assume the sketch came before the diary entry. It is unclear whether it is an image from his mind or someone he saw in person. The subject of the sketch either has their eyes closed or is looking downwards with relaxed but almost upset expression. Here could be a direct visual insight into Lawford’s day along with the diary entry. Crucially, this entry shows how the middle and upper classes were able to enjoy leisure time even during the war, something most could not dream of during this period.

The Papers of Valentine Lawford, LWFD 1

Diary of Mary Agnes Hamilton, 12th March 1941

Mary Agnes Hamilton, a Labour MP for Blackburn from 1929-1931, was one of Britain’s earliest female politicians holding a role at the forefront of British politics in Parliament. During World War Two, Hamilton would hold several key positions - at the time of this diary entry working on the Reconstruction Secretariat. Her diary illustrates the centrality of her daily life to the nation’s administration and war effort in devising a ‘consensus policy on general unemployment’ alongside renowned liberal economist John Jewkes. Yet Hamilton’s entry also offers a uniquely personal perspective on the high politics of war. She describes her own, ‘great excitement’ as an observer of Conservative politician Arthur Salter’s shipping mission to Washington. This anticipation would prove substantiated as the event would become crucial in drawing the United States into the construction of a post-war pan-European government. Rather than offering a detached perspective on events, Hamilton’s diary is indicative of the emotions of the political world. She depicts the strain that political life could play on family relations, noting how her university friend Ethel Bullard, ‘hated’ the prospect of the Washington mission and that her departure would be, ‘very hard on her sister’. Such a distinctly intimate perspective of political responsibility illustrates the humanising lens through which diaries allow observers to understand those in otherwise distant positions of power. Notably, Hamilton herself describes how she will miss her long-time friend, ‘very much’. Furthermore, Hamilton ends her entry with a description of overnight bombing. A tangible anxiety and subsequent relief are notable in her depiction of limited damage in London. However, the brevity with which such a, ‘nasty loud night’ is described also illustrates how danger had become an ever-present aspect of civilian life. The nature of Hamilton’s treatment of London bombing can be noted throughout her diary.

“Great excitement as Arthur Salter is to go at once to US to look after shipping there; she too. He had long talk with PM on Sunday and they expect to go at the end of next week. Luckily she still has her house in Washington. She says she hates going: it is certainly going to be very hard on her sister. I suppose they may be there for the duration. I shall miss her very much. Indeed the progressive impoverishment of one’s life proceeds in horrible crescendo. I miss Ray more and more: Ethel going will make another gap. Nasty loud night, though few bombs on London. A huge and brilliant moon.”

Papers of Mary Anges Hamilton, HMTN 1/6

Diary of Mary Soames, 14 September 1939

This extract has been taken from the diary of Mary Soames, the youngest daughter of Winston Churchill, on the eve of her 17th birthday on September 14th, 1939. Only 11 days prior, Neville Chamberlain was addressing the nation and announcing to millions that Britain was now at war with Germany. She was now facing a global war as a young girl at the start of her life.

Mary’s diary provides a unique insight into the effect that the tumultuous political climate was having on young people. The entries are incredibly personal and draw into her thoughts, and emotions. Diaries like hers are necessary for modern audiences to understand and empathise with the human nature of war. As evident in her diary entry, Mary possesses a genuine fear that she ‘may never know another happy day in [her] life’.

Her hopelessness is very poignant and contrasting to the Keep Calm and Carry On view that many have of the war effort. She quotes a play by Noel Coward called Cavalcade and draws comfort from the ‘spirit of gallantry and courage that made a strange Heaven out of unbelievable Hell’ which lies in the human soul. It is inspiring to see that despite the world she found herself living in, she still has love, and the hope that she will make it out of this – albeit a changed woman. Mary’s diary not only captures her raw emotions but is the closest one can get to living as a young girl in 1939.

“The last day of my 17th year. Tomorrow I shall be SEVENTEEN. I can scarcely believe it! The years have flown – 7 and then 17 – the years between seem like fleeting shadows that passed quickly, happily. I may never live to see another year – I shall never see the world again as I knew it before this bloody war. But if I were never to know another happy day in my life – (and I know that I shall probably do that, because in the human soul there is that ‘spirit of gallantry and courage, that makes strange heaven out of unbelievable hell’) but if I may never know happiness or joy again I shall always have the memory of my first 17 years – a golden, glowing memory of pleasures, loves, friendships and heavenly rapture of living at peace in the beautiful place that is my home.”

The Papers of Mary Soames, MCHL 1/1/1

Group D: Diaries of Alexander Cadogan

By Patrick Courtney, Evie Ridler, Hattie Seager-Pope and Shannon Webb

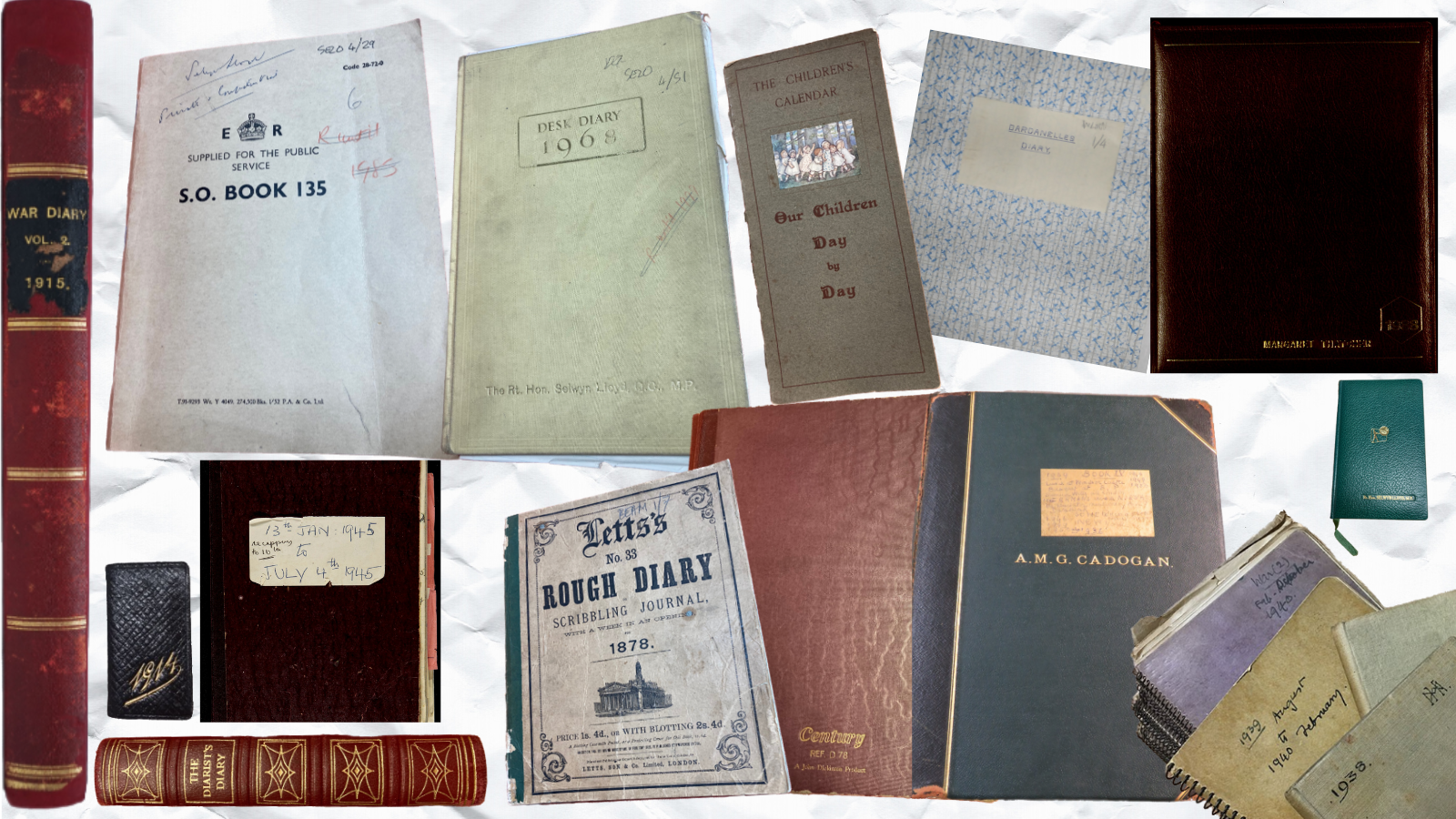

Diaries of Alexander Cadogan, 1936 and 1937

Sir Alexander Cadogan was a British diplomat and a civil servant. He was the Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs and accepted a position at the British legation in Peking, China. His time in China is well documented in his diaries and he purchases diaries to use in China.

The 1936 diary, as seen in the picture that is a dark beige colour with a black strip of tape along the left side of it, was bought in China. Cadogan brought it from the Yung Hsing Stationery Company. Looking at the condition of the diary itself shows that he did use it and handle it a lot, there are frayed and rubbed edges all along the side of the diary. There is also some stain marks and a rip up the middle of it. The condition of his diaries is interesting, it shows that he used them a lot, he wrote in his diaries every day.

The 1937 diary, which is blue with gold writing on the front, was bought from the Onoto Pen Company in the UK. The 1937 diary has quite a lot of damage. There is no spine on it, this has caused the front cover to become unattached, there is also a lot of discolouration along the sides of the front cover due to it not being intact. The condition of this diary and how the front cover came off is unknown. It may be because Cadogan was an avid writer and used his diaries a lot.

Looking at the conditions of diaries is important as it shows how people cared for them and how much effort went into writing in them and how it was a big part of their life. Cadogan’s diaries were obviously well used, and this reflects in their condition today.

Alexander Cadogan’s 1936 diary

Reference ACAD 1/5

Spine missing from Alexander Cadogan’s diary for 1937

Reference ACAD 1/6

Diary of Alexander Cadogan, 2 February 1943

Sir Alexander Montagu George Cadogan was a British diplomat and civil servant. He worked specifically as Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs from the years 1938 to 1946. Throughout his time in this role, he kept daily diaries. Many include strong opinions and his criticisms towards British policies and in some cases towards particular members of government.

Key points throughout Cadogan’s career include his service at the Versailles Peace Conference and later becoming the head of the League of Nations section of the Foreign Office in 1923. He also held strong views on appeasement policies of the 1930s. But could see how there were limited options for Britain at the time.

The diary of 1943 in particular contains daily accounts of events, meetings and a general opinion on foreign affairs. In particular the diary account of Tuesday 2nd of February was particularly interesting. This account states what tasks he completed throughout his day, but most interestingly he speaks of sitting between ‘Churchill and Randolph’. He then goes on to state how he felt about the latter of the two, (Churchill’s son Randolph) was ‘coarse and bumptious and conceited and stupid’. This severe name calling and hatred towards Randolph is extremely gripping. Also, the fact that Cadogan made this written knowledge rather than expressing his views verbally to someone suggests how strong his feelings were, but also how he was quite a passive character who wouldn’t have been afraid for his diaries to have been read by others, both at the time or in years to come.

Extract from Alexander Cadogan’s diary, 2 February 1943.

Reference ACAD 1/12

Typescript summarised version of an extract from Alexander Cadogan’s diary, 2 February 1943

Reference ACAD 1/45

A page from Alexander Cadogan’s diary for 1950, covering 24-26 January

Reference: ACAD 1/21

Alexander Cadogan’s diary, 24 January 1950

There are two extracts that highlight the recognition of Communist-China in 1950, January 12th and January 24th. This will focus more on the 24th of January 1950.

Cadogan mentions “Tsiang”, referring to Tsiang Ting-fu, who was a very crucial figure in the rise of Communist-China and the United Nations. He served as China’s first ambassador to the United Nations; and he wrote enormously on issues from the role of the Chinese peasantry to the post-war Attlee government in Britain.

The mention of China and Russia forming a rival organisation could cause great concern for Britain and other Western superpowers. For Britain at the start of the decade, this worry of communist China allying with Soviet Russia could cause anxiety for America and the cold-war situation as well as trading imports/exports with China. Soviet influence in China was advancing, as expected by Britain during this period, China and the Soviet Union signed a Treaty of Mutual Assistance in February 1950, following on from a visit by Mao to Moscow in December 1949. This was a growing concern for Britain due to the occupancy in Berlin being split between Western Europe and the Soviet Union. These close connections may create a problem for Britain later if China and Russia form this rival organisation. Moreover, there was a rise in Fascism in Britain in the 1950s, thus, the recognition of Communist-China would have caused great concern for the British government.

This is significant for a historian or the general public because, the extract can be used to explain the impact of these communist powers expanding on Britain and its Government. Furthermore, this extract can be used to explain the tensions between Communism and Capitalism as well the use of the UN on these countries.

Alexander Cadogan’s diary, 1952

This diary is specifically useful for someone who would like to look through the lens as a British diplomat.

Cadogan would have been an upper-class figure during this post-war period, with close connections with governmental problems and individuals, as demonstrated by previous diaries. This specific dairy will be useful to get an insight into his lifestyle and what he did outside of work and meetings.

Throughout the diary, Cadogan plays a game called Canasta, very frequently throughout his life in the 1950s. The game is a card game, like what we know as Rummy today; it became rapidly popular in the United States and other countries in the 1950s. Therefore, indicating what someone of this class would do for fun, in their free time.

There is also a large focus on cocktail parties during the 1950s era. This not only highlights the upper-class lifestyle but also is significant when looking into rationing. Due to rationing still occurring during the 1950s, cocktail parties became a better alternative because it required a less extensive menu than a dinner party. Thus, demonstrating how rationing had an impact and how the upper-class adapted to these rules, post-war.

Cadogan also has a large focus on the weather throughout his diary and in many other of his diaries. Though this doesn’t feel relevant to the reader, this small detail each day suggests the audience for his diary was only himself. The language implies he didn’t write his diary with the intention of others reading it. Additionally, the weather also creates context for his day, for example it might explain why he had completed certain activities due to weather related problems. As a result, emphasising the significance of his diary when enquiring about life in the 1950s, specifically as a British diplomat.

The Papers of Alexander Cadogan, ACAD 1/23

Alexander Cadogan’s diary, 30 October 1956

In 1956 the Suez Crisis engulfed Egypt as a result of the nationalization of the Suez Canal. The canal was previously owned by the Suez Canal Company which was controlled by Britain and France. Sir Alexander Cadogan was on the Suez Canal Committee at the time. Cadogan’s writing on the crisis reveal his negative opinions on the likelihood of British success. He thought that success would only come if there was a quick decisive victory.

When Cadogan learnt of the ceasefire in Egypt the only comments he made in his diary were simple comments stating he didn’t really know what this meant showing some of his detachment from politics.

Diaries of people at the fringes of events like Cadogan was at this point in time can often offer a more candid view of the events such as Cadogan’s negativity on the Suez Crisis. At this time in his life Cadogan had largely put his political career behind him and was instead working as Chairman of the Board of Governors of the BBC. His 1956 diary has much more of a focus on his BBC work and his pastimes like working on his garden and an interest in art with even big political events like the Suez Crisis taking a backseat. This paints a very different image of the man who was immersed in the political world when he was younger. Diaries like this one that show people at the end of their careers can be interesting to get a view of what their own thoughts about their careers could be. Cadogan seems to have been able to put politics behind him for the most part and find new passions late in life.

An extract from Alexander Cadogan’s diary, 30 October 1956.

Reference: The Papers of Alexander Cadogan, ACAD 1/27

Group E: First World War Diaries

By Megan Davies, James Klima and Adam McEwen

Bickersteth Diary

This is the diary of Ella Bickersteth (1858-1954) which includes accounts of her family’s experience of both world wars. Ella married Reverend Samuel Bickersteth in 1881 with whom she had 6 sons: Monier, Geoffrey, Julian, John (who worked with Maurice Hankey in the 1930s), Morris (who died during the First World War), and Ralph. Since she was the wife of a clergyman, she would have been a prominent figure in her parish and local area in Canterbury. Her family had strong ties within the British Empire; her paternal grandfather was a Surveyor-General in Bombay, his father-in-law was a member of the East India Company. Ella’s father, Sir Monier Monier-Williams, was Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University and was knighted in 1886.

On the 2nd of August 1914, Ella and her family were on holiday in St Ives and got to witness the naval reserves departing. She recounts attending church that morning and listening to the Vicar pray ‘for the preservation of peace’, there was a feeling of being ‘on the brink of one of the greatest catastrophes the world has ever seen’. She describes the reserve’s departure and the ‘grave’ and ‘restrained’ mood, a direct contrast to the peace celebrations in 1918. Ella Bickersteth also provides a picturesque description of how the bay ‘glittered in the sunlight’ as well as the scenery of the fishing boats and villages of Cornwall. And claims this was ‘surely a bit of English life worth fighting to preserve’, reflecting the sentiments of many British people in 1914.

The Bickersteth diary has a scrapbook element as it includes photographs, postcards, newspaper clippings, telegrams, and letters from the Front. This provides us with a unique combined military and civilian perspective. Since it was written on a typewriter and even includes page numbers and a timeline, it is legible, thought-out, and likely written later with hindsight and perhaps with intent to be read.

Postcard found in BICK 1/1

Page 6 of volume I of the Bickersteth War diaries, August 1914

Reference BICK 1/1

Page 7 of volume I of the Bickersteth War diaries, 2-3 August 1914

Reference BICK 1/1

Disease and War: Geoffrey Harper

Geoffrey Harper (1894-1962) was a Royal Navy officer who wrote this diary in the era of the First World War. Harper was a man who cared deeply about privacy and censorship; this appears in the opening page of his diary, where he says this book is ‘private, serious and confidential’! This work is his diary which he has handwritten on his own.

Harper is in some ways the stereotype of a Royal Navy officer; he writes about partying at the end of the war in this book as something which was ‘spontaneous, unorganized and undisciplined’. However, this was not something he disapproved of; in fact, Harper found the celebrations at the end of the war to be a remarkable thing. He talks about how ‘the scenes last night were beyond description’.

When Harper returned from some time at sea, he wrote about what he saw in Edinburgh at the end of the war on Princes Street. He saw how all the celebrations blocked up the street, and he thought the whole thing was ‘extraordinary’.

What Harper mentions in this diary, which is interesting concerning our modern world, is the issue of the influenza epidemic during a time of war. This is particularly topical with the situation in our modern world. We are only now starting to recover from the Pandemic of our time. Furthermore, at the time of writing, we see the most significant conflict in Europe since the World Wars unfold in Ukraine.

There are many exciting details in this diary that tell us about the period; for example, when Harper mentions that the regular sailors received rum to celebrate, the officers would receive champagne. This displays the importance of class and rank, which were very interlinked in the Royal Navy and the First World War.

Harper went on to fight in the Second World War when called upon and eventually settled down in South Africa; he died on the 1st October 1962.

All three images taken from the Papers of Geoffrey Harper, HRPR 1/11

Maurice Hankey

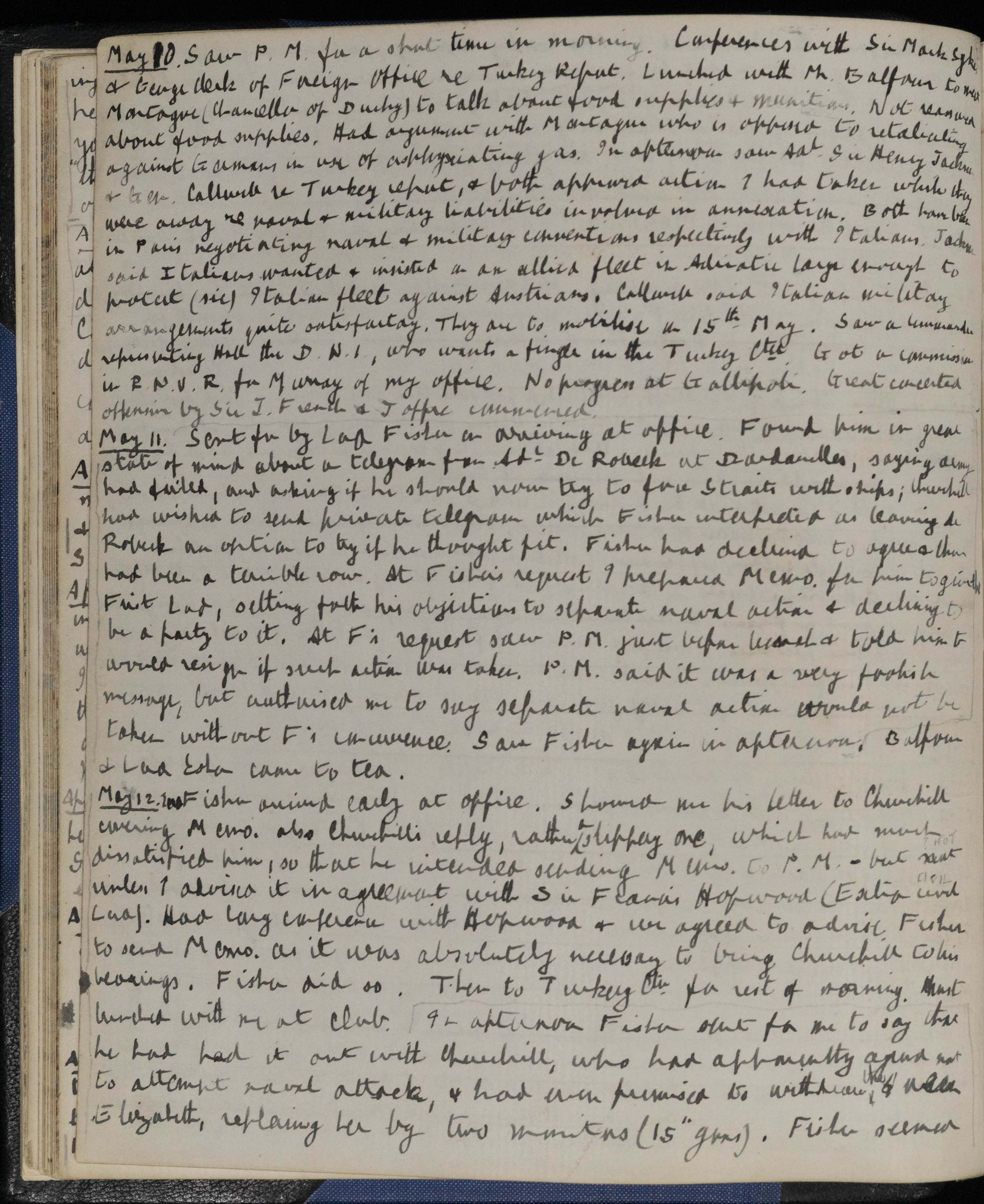

Maurice Pascal Alers Hankey (1877-1963) was Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence, Secretary to the War Council during the Great War, and the first Cabinet Secretary. He kept a diary starting in 1915, handwritten for the first month by his wife Adeline who he refers to as his ‘amanuensis’. This changes in April, with Hankey writing the remainder of the entries, with a few exceptions, possibly because of his frequent separations from Adeline. The handwritten entries are legible with the opening statement using pen in Hankey’s handwriting explaining the diary’s purpose with Adeline’s first entry opposite in a different ink.

Looking at the entries Hankey uses this diary to record the minutes of Cabinet meetings; this was because no official minutes were recorded until December 1916, with only cabinet memoranda at this time. Later entries start to become shorter and less detailed, reasons for this could range from prioritising only important points through to simple disinterest, these short entries also have their opposite with occasional pages being just a wall of text. One difficulty with some entries particularly the shorter ones is an implied understanding of terms and people, pointing to this diary being written for a specific audience. For March 26th -27th 1916 loose pages have been inserted showing Hankey did not always have his diary on his person and throughout the diary amendments and corrections have been made in different pens and handwriting showing that Hankey possibly went back through making corrections and additional points.

Hankey’s motivations for keeping this diary are unclear, there are no personal entries except minor complaints like a French translator being a distraction and it is not a memoir; he possibly wrote it to reflect on the war years and the difficult and important decisions that needed to be made over that period.