The Boat Club and the Canon

In 1961, the Churchill College Boat Club was founded.

61 years later, we’re celebrating the club’s foundation, its successes, and the role played by Canon Noel Duckworth, the College’s first chaplain and avid amateur rower.

Foundation

The Churchill College Boat Club (CCBC) was founded in the same year that Churchill College admitted its first intake of postgraduate students. The College itself was still under construction so the club had no boathouse of its own but instead shared with the City of Cambridge Rowing Club.

This arrangement lasted until 1968 when CCBC moved to a new boathouse, sharing it with Kings College, Selwyn College and The Leys School. This arrangement remains the same today with the Colleges and school sharing facilities and staff.

One of the driving forces behind the foundation of CCBC was Churchill College’s first chaplain, Canon Noel Duckworth. He joined the College in 1961 and was co-founder, coach and treasurer to the CCBC from then until his retirement in 1973.

Noel Duckworth: the rower

Noel Duckworth was educated at Lincoln School before coming up to Jesus College, Cambridge to read History in 1931. As an undergraduate, he soon became involved in rowing, going on to cox the winning Cambridge crews in the annual Cambridge/Oxford Boat Race in 1934-1936. In 1936, aged just 23, he also coxed the Great Britain eight at the Berlin Olympics - the crew came fourth. The College Archive has his Olympic cap.

While Noel undoubtedly had a passion for rowing, his studies took him in a different direction and after reading Theology at Ridley Hall, he was ordained in 1936.

Canon Noel Duckworth: at war

With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Canon Noel Duckworth was appointed Chaplain to the 2nd Battalion, Cambridgeshire Regiment and deployed to Malaya in 1941. In January 1942, the battalion and others were defending Batu Pahat when they were ordered to withdraw to avoid being cut off by the advancing Japanese forces. Canon Duckworth chose to stay behind with the wounded and was captured at Senggarang.

As recounted in The Naked Island (London, 1952), Braddon recounts that “[Noel] stayed there and when the Japanese […] would have slaughtered the wounded, this little man flayed them with such a virulent tongue that they were sufficiently disconcerted to refrain. They beat him up very cruelly for days, because they did care for being verbally flayed […] but they did not kill the wounded men he had stayed behind to protect”.

In Canon Duckworth: An Extraordinary Life (Cambridge, 2012), Michael Symth (U63) suggests why Canon Duckworth was not himself killed: “When Noel was captured with the wounded soldiers one of the doctors who had also stayed behind attested “I firmly believe that Noel’s fame as a rowing man saved all our lives” because a Japanese officer recognised Noel. This story is given some credence by the fact that a Japanese crew from Tokyo University participated in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, as well as Henley prior to that, so it is likely that Duckworth was known to them”.

Later in the war, Canon Duckworth was moved to Changi Gaol before being sent in 1943 to Thailand and Burma to work on the notorious Burma Railway. He was one of the very few who lived to return to Singapore in April 1944. Recognition of his wartime achievements came in 1946 when he was retrospectively mentioned in despatches for “gallant and distinguished service while a prisoner of war” and “in recognition of gallant and distinguished service in Malaya in 1942”.

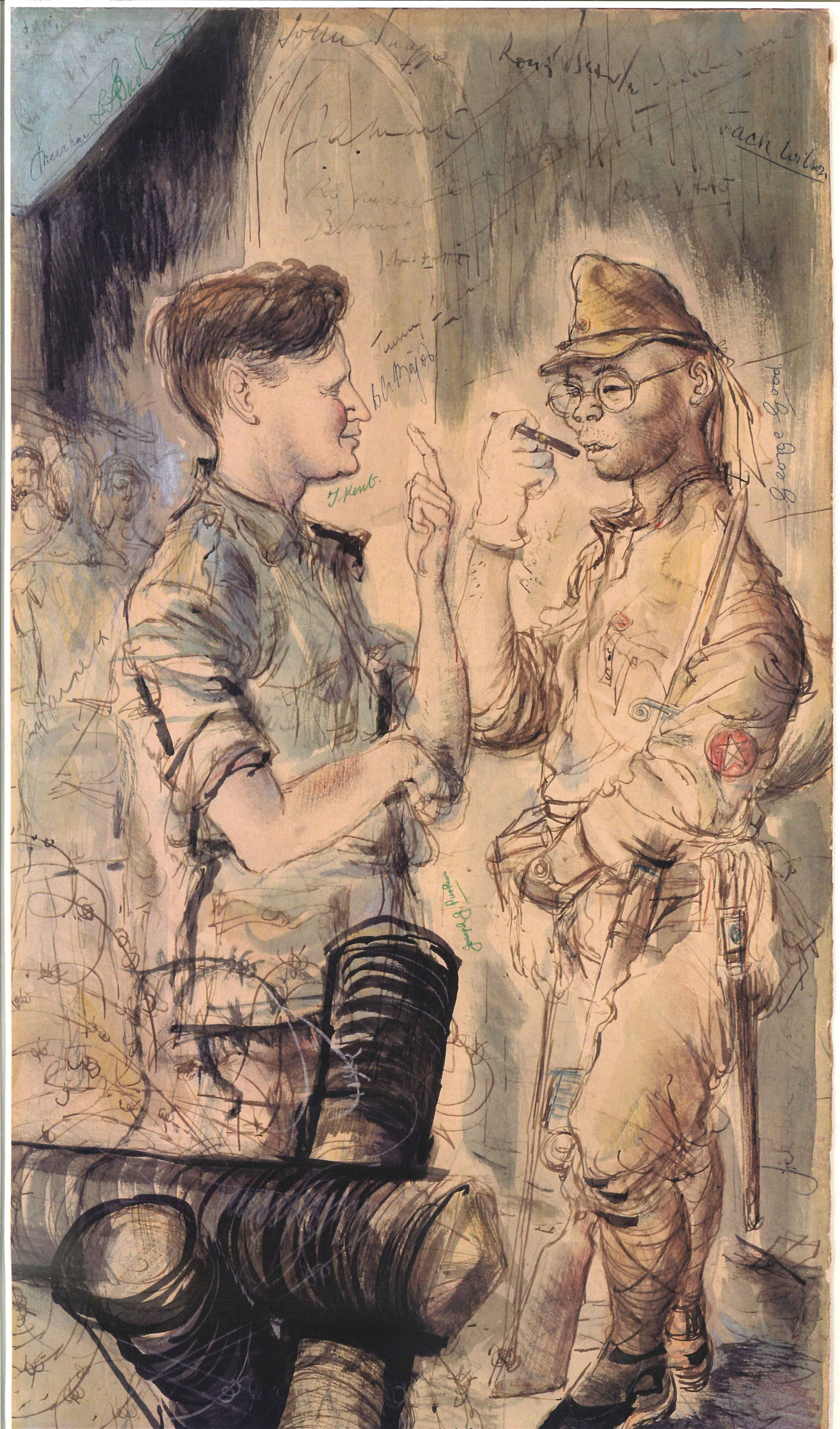

Image created by Ron Searle, depicting Canon Duckworth negotiating with a Japanese soldier.

From Asia to Africa and home again

His adventures in the Second World War did nothing to dampen Canon Duckworth’s interest in travelling and living overseas. He lived in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) 1948-1957 where he helped to set up the first university in that country before returning back to the UK to take up the post of Chaplain at Pocklington School, Yorkshire.

It was from there that, in 1961, Canon Duckworth joined Churchill College as our first Chaplain. Once back in Cambridge, he soon set about founding the CCBC.

Canon Noel Duckworth: the coach

By all accounts, Canon Duckworth was neither an archetypal clergyman nor coach but full of enthusiasm, excitement and persistence. The image adjacent shows the Canon coaching the CCBC with his megaphone and stopwatch, which the College Archive also has.

The CCBC website has a section on memories of the Canon, from which the following are taken:

He was just as happy coaching the fourth boat as well as the first and was almost solely responsible for the tremendous progress that Churchill made in the early years. Bumps and overbumps were almost completely routine and if a Churchill boat was bumped it was a College tragedy.

M. Bomford

We were a small band but rapidly became a force on the river. The boatclub became a potent symbol of collegiate life even before we had the buildings that make up a college. That was Noel Duckworth’s achievement.

H Davies

He was capable of almost apoplectic excitement and regularly cycled into the river during races

A Ramsay

He also had his own unique language, happily captured by What the Coach meant to say (Churchill College Archive, CCRF 151/34) and expanded on the CCBC website.

After many happy and successful years at Churchill and on the river, Canon Duckworth retired in 1973.

Help the College Archive

If you have any photographs or documents (physical or digital) about the Boat Club that you would like to donate to the College Archive (either now or in the future), please contact the College Archivist (college.archivist@chu.cam.ac.uk). The College Archive relies on donations from students, staff, Fellows and alumni for its holdings on social and sporting activities.