Listening in: everyday stories of science and technology

Diaries

By their very nature, diaries take us directly into the daily lives of their authors. Whether they are perfunctory, detailed, observational, or introspective, the diaries in our collections touch on many aspects of human experience in the twentieth century, including our encounters with rapid changes in science and technology.

We “listened-in” for the first time

On 19 January 1925, Ian Jacob and his wife Cecil noted in their diary that they had ‘ “listened-in” for the first time’ to their new ‘crystal set’. They had acquired the crystal set from ‘R.I.’ (Radio Instruments Ltd) and were using it to tune in to Chelmsford. This Essex town was where the newly formed BBC broadcasted radio programmes via the longwave transmitter developed by the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company. It’s not surprising that the Jacobs were early adopters of the radio: they were a wealthy young couple with a comfortable domestic life and Ian was an army officer in the Royal Engineers whose work brought him into close contact with new technologies. He would go on to a notable career in military intelligence, communications and propaganda. In an even neater piece of foreshadowing, he would later oversee the fortunes of the BBC as its Director-General for most of the 1950s.

Reference: Ian and Cecil Jacob’s diary, 1924-5 (JACB 1/2)

Everybody is concerned about Cuba

In October 1962, another couple was listening in to the radio during the Cuban missile crisis. In a long diary entry, social researcher Phyllis Willmott records the reactions of family, friends and strangers to news of the nuclear confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. She analyses the existential anxiety of living in the atomic age, worrying about ‘my diaries, all 20 years of them, vanished along with ourselves and all we know’. She explores her feelings about the agency of the individual and the power of collaborative action to oppose the proliferation of nuclear weapons and advocate for global disarmament.

Reference: Phyllis Willmott’s diary, 1962-3 (WLMT 1/25)

Letters

Letters in the collections of scientific experts and ministers show us how ‘ordinary’ people made their voices heard. People of all ages put pen to paper to share their opinions, hope and fears of scientific and technological change. Experts addressed these uncertainties in their own letters, by advocating, reassuring and explaining.

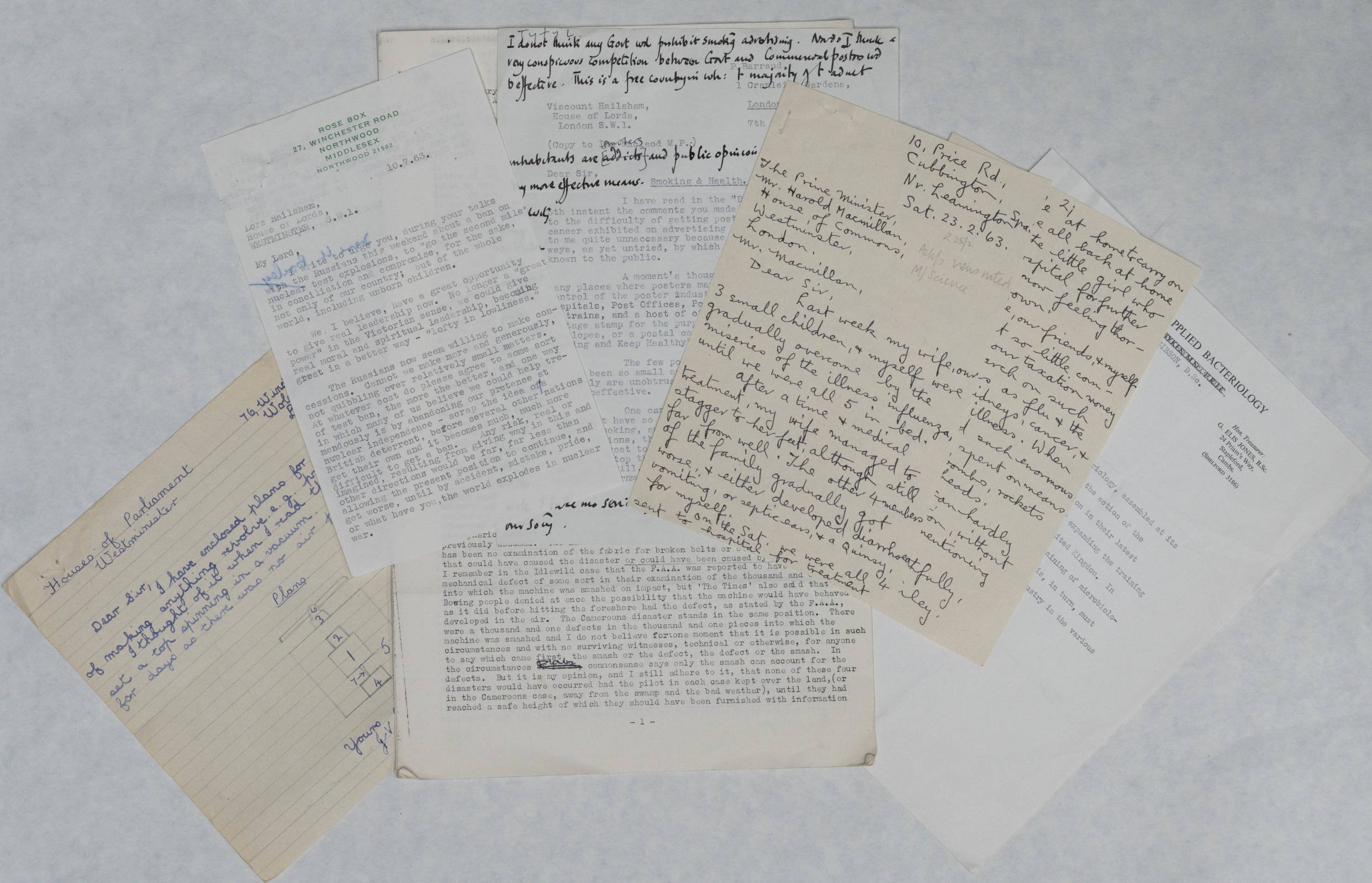

A Minister’s postbag

A handful of letters shown in the photograph opposite are from one of the sixty files sent to Lord Hailsham when he was Minister for Science and Technology (1959-1964). The letters are penned by individual members of the public and organisations and illustrate a range of subjects covered by his correspondents. This small selection includes letters about a nuclear test ban treaty, regulation of tobacco advertising, funding flu research, civil aviation safety, teaching science and engineering in universities, and a design for a machine sent in by an eleven year old. Read collectively the letters in a politician’s postbag are evidence of individuals’ responses to public statements, policy initiatives, proposed legislation, and news coverage of global events. Read by themselves, they give vivid testimonies of personal experience and biography.

Reference: Lord Hailsham’s correspondence file, 1962-3 (HLSM 2/10/2)

A scientist’s postbag

The correspondence of Robert Edwards, pioneer of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), tells us a lot about Edwards and the team’s scientific research, as well as the political, legal, religious and social reactions to that research and the development of IVF.

Edwards’ letters show us that as well as carrying out scientific research into reproductive technologies, he was involved in explaining the need for the research and in advocating for universal access to IVF.

For example, in this letter to Cambridgeshire Area Health Authority (October 1981), Edwards argues that the NHS should fund IVF treatment for patients.

I would be interested to know the current ethical and legal situation arising out of our desire to treat them, and their desire to come to us…It does seem to me that a serious situation has developed, because these patients have paid their contribution to the N.H.S. and, now they want treatment, they are not being allowed to receive it.

Cambridgeshire Health Authority replied to Edwards’ appeals for support, ‘Our current allocation is insufficient to maintain the service that we already provide. There is, therefore, no way in which the Health Authority can meet the expense of NHS patients attending your clinic.’

The Edwards collection contains 53 boxes of correspondence (out of a collection of 141 boxes) and there are sections of “general correspondence” as well as sections which relate to specific topics such as legal matters (mostly lawsuits against newspapers) or publicity.

Reference: Robert Edward’s correspondence file, 1981 (EDWS 1/1/1/54)

Photographs

Itself a technology that transformed how people remembered and archived the everyday, photographs in the Archives Centre show a personal side to the life and work of scientists in our collections. Family photographs or holiday snapshots question the image of a lone genius, showing experts embedded in community and family networks.

Photographs of everyday life in an extraordinary place

The Papers of Egon Bretscher contain colour photographs of life at Los Alamos, New Mexico, home to the Manhattan project which developed the first atomic bomb.

Through his work on nuclear physics, Bretscher was involved in the British atomic bomb research project “Tube Alloys”. He also became a member of the British Mission to the Manhattan District Scientific Laboratory at Los Alamos. He worked at Los Alamos in Enrico Fermi’s Advanced Development Division from 1944 to 1946.

The photographs in Bretscher’s archive show the everyday life of the scientists who worked at Los Alamos, their families, and the local community.

These photographs show Egon Bretscher with Mr Pena (Jan 1946); Hanni Bretscher (Egon’s wife) and Edward Teller when climbing Lake Peak [in Sante Fe National Forest] (Jul/Aug 1946); Hanni Bretscher at Navawi ruins [near Los Alamos] (Apr 1946); the Los Alamos Trading Post (Oct 1945); and Egon Bretscher’s family waiting to collect Egon from Del Monte Ranch (Oct 1945). The title image of this exhibition shows the guard house at the entrance to the Manhattan Project (Oct 1945).

Many of the scientists in our collections share the Bretscher’s love of hiking including Rosalind Franklin (x-ray crystallographer who studied the structure of DNA and viruses) and Lise Meitner (nuclear physicist who co-discovered nuclear fission).

Reference: Photographs of Egon Bretscher, 1945-6 (BRER A 62a)

On the road

Photographs taken of Ernest Marples during official visits as Minister of Transport (1959-64). These highly staged photo opportunities still afford the viewer glimpses of the workplaces and environments in which people lived their daily lives. They document changes in architecture, urban planning and transport and are suggestive of the shift to post-war car culture and a world of motorways, flyovers and shopping malls. An image can provide evidence that is otherwise missing from documents and textual sources and elicits imaginative responses and interpretation.

Reference: Photographs of Ernest Marples in Germany and the United States, 1959-64 (MPLS 3/6/1, 3/6/8)

Campaign Literature and Printed Ephemera

Not all experience of scientific change was positive. The existential threat posed by nuclear weapons galvanized a popular protest movement for disarmament. Posters, leaflets and other campaign literature gives us a vital look at how people resisted scientific-military technology.

Do’s and Dont’s for Marchers

A montage of leaflets and printed ephemera from the collection of biologist and peace activist Michael Ashburner. This selection of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and Committee of 100 literature only found its way into an archive thanks to the efforts of one individual who recognised its historical significance and preserved a type of material that is so often thrown away. The collection illustrates the broad range of people and groups - often involved in other human rights and political campaigns - who came together in the anti-nuclear movement. It documents the issues they campaigned on, such as nuclear weapons tests and fallout, and their strategies of marches and sit-ins targeted at military facilities like the submarine bases in Scotland, airfields in England, and particularly the headquarters of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston. And it takes the researcher deep into the tactics, logistics and practicalities of protest, from maximising the impact of an action to wearing sensible shoes.

Reference: Michael Ashburner’s leaflets and printed ephemera, 1950s-60s (ASHB)

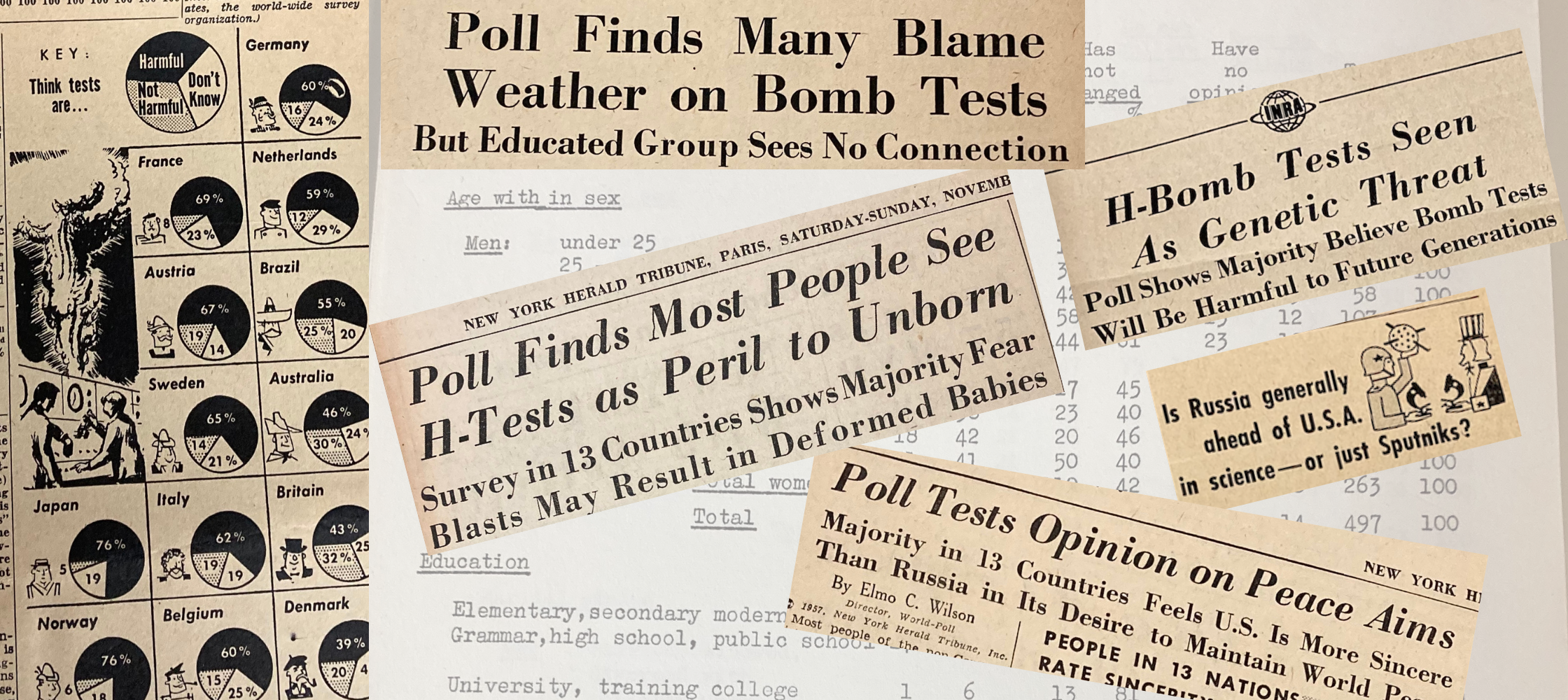

Polling Data

Another source of popular opinion of scientific change in the nuclear age comes from polling data. Social scientists collected data from a public coming to terms with the new threat posed by atomic weapons. The questions asked and answered give us a glimpse into the mass uncertainty and confusion surrounding nuclear technology at the beginning of the Cold War.

International Opinion Polling, 1957-8

We also hold papers which allow us to measure public opinion in the atomic age. In the collections of the market researcher Mark Abrams (1906-2004), we hold the original working papers and results from various polls conducted in the UK and Europe by International Research Associates in New York during the late-1950s.

In May 1957, the first British hydrogen bomb had been exploded on Christmas Island, and Britain’s first successful thermonuclear bomb was launched in November of the same year. A fire in one of the core reactors, also in November, had resulted in clouds of radioactivity being transmitted into the atmosphere. Unsurprisingly, the launch of the bombs was the frequent subject of public commentary during the late-1950s.

Here’s just some of the questions asked by pollers to those living through the height of the atomic age:

Some people say that the climate of this country has been changed by atomic experience. Do you believe this or not?

Some people claim that hydrogen bomb explosions are endangering the health of future generations. Do you believe this or not?

Which political leader or statesmen is making the great contribution to the achievement of peace today?

The answers to these questions are recorded by gender, age, level of education, and environment (rural and urban), allowing for interesting comparison both within groups in the UK and in Italy.

“Scientists have warned society about the H-bomb. Obviously, it is a dangerous play thing.”

“I believe a lot of scientists are upset about H-bomb testing and are afraid to say so”

“This matter is one for the scientists to decide. There may be danger if these explosions go on. The tests should be stopped - but not on Russia’s conditions.”

Reference: The Papers of Mark Abrams, ABMS 5/20

Reference: The Papers of Mark Abrams, ABMS 5/20

Audio Recordings

Oral histories, like the ones presented below and preserved in our collections, provide unique access into ‘ordinary’ people’s experience of rapid scientific change over the twentieth century. Recorded life histories show how technological change profoundly shaped people’s lives, work and families over the course of the century.

On the air

This radio programme from Oldham Hospital radio relates to the history of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). It was recorded following Oldham’s Innovation Exhibition event held in 1999 to celebrate 21 years of IVF and 21 years since the IVF first baby (Louise Brown) was born.

The programme includes interviews of the scientist behind the scientific breakthrough (Robert Edwards), as well as of the parents of the first IVF baby (John and Lesley Brown) and of Louise Brown herself. These interviews reflect on the interviewees’ experiences of science, how it changed their lives and other peoples’ lives as well.

A slightly unusual archival document, this recording can be used as a source for the history of the development of IVF and the impact on individuals and society of the success of the technology.

Reference: radio interview with Robert Edwards, 1999 (EDWS 19/3)

I was born in December 1895

Towards the end of his life, Thomas Elmhirst recorded twelve audio cassette tapes of reminiscences. In this extract from ‘Childhood’, he describes the living conditions of his large middle-class family, including cramped housing, basic sanitation, infectious diseases, water supplied from a well, and lighting by paraffin lamps and candles. All transport was horse drawn and he precisely recalls his first sighting of a car in their East Yorkshire village. The car would only be the beginning for him, as he went on to learn to fly airships in the Royal Navy and aeroplanes in the Royal Air Force. His retrospective recordings give glimpses of the transformative effect of science and technology on the material circumstances of many people’s lives in the twentieth century.

Open the door to our collections

Browse our thematic research guides

Search our online catalogues

Find out about our copying and research services

Make an appointment in the reading room

Ask us a question at archives@chu.cam.ac.uk